This is a transcript of a Distinguished Seminar Series talk I gave at OCLC in Dublin, Ohio in November of 2017. It’s edited somewhat for clarity and I’ve removed verbal fillers, eliminated a few random asides, and restored compressed content. This took me the better part of a year to finish, and while I’m trying to not have judgement about that the upshot is that I am my own worst transcribing nightmare. Put another way, it’s incredible how many words one human being can cram into 60 minutes.

Some themes and resources in this talk are consistent with the Social Justice Summit posts I shared some time ago, but stick with it and the content will diverge/clarify. The video is below and you can see the slide deck if desired. A reference/works consulted list follows at the end.

For the Greater (Not) Good (Enough): Open Access and Information Privilege

The title of my talk is For the Greater (Not) Good (Enough): Open Access and Information Privilege. This is a lot of heavy stuff, right? Open access (OA) is a huge topic, information privilege is a huge topic. What I want to do is begin with an image that I think can sum up how I’m going to come at these two giant ideas, both of which can be a little – let’s face it – depressing.

This is one of my favorite images. I took it in West Texas – I’m from Texas originally. I was driving through this little tiny ghost town on a sad highway, and the oil industry had dried up at this point – this was about 10-12 years ago. There was a lot of economic degradation, and you could tell there were not many opportunities available. Yet there was an old sign printing shop that somehow, someone had taken the time – in this store that didn’t even look like it was operating – to put up this message (“happiness is attainable”) letter by letter even though the thing’s rusted and the town’s falling apart.

The incongruity of this has always struck me as amazing. It’s it’s a way to encourage ourselves to acknowledge that there are hard things but that there are also very positive, resilient messages that can be seen within the challenging spaces. So remember that sign no matter how heavy I get. I promise that I’ll wrap it back around to this place by the end of the presentation.

Before I get any further I want to say so many thanks to OCLC for having me here – to Rachel (Frick) of course – Lorcan (Dempsey). Also, Nancy Lenssenmayer is literally the most effective person I have ever worked with in my life. She’s amazing. Thank you, Nancy. I also want to thank all the people who came today, all the people who are online spending the time to listen to this talk and hopefully ask some good questions after I’m done spewing up here. And thanks of course to all the people who have inspired this presentation. There have been a lot of scholarly communications librarians that I’ve worked with over the course of my life – I am not one – and I’ll talk a little bit about that in a moment. First off, of course Carmen Mitchell at my own institution, CSU San Marcos. I have learned a lot from her. I also want to give a shout out to Amy Buckland, and also to Allegra Swift who works at UCSD. Thank you for all the learning that you’ve helped me do in preparation.

Back to the presentation. It’s wonderful to be invited to this series. As Rachel mentioned, I started my career at Ohio University as a librarian. It was my first job, and this is the cabin that I lived in the woods in the complete sticks north of Athens [referring to slide 8]. I loved it there. One of the things that was interesting about having this as a first job is that I was indoctrinated into the collaborative library culture of Ohio, which is fierce. For those of you who have been here for a long time I see some head nods – OCLC was established back when the first word in its name was “Ohio” to begin a process of harnessing collective energy through collaborative cataloging. The library I was in had memories of that as OCLC’s original role. That harnessing of the collective energy of our profession is something that is very central to what I’m talking about today. The need for it and the continuation of it, particularly in a non-profit space, and a space that does not have a profit imperative or a profit motive. Because we are libraries and librarians, and we do not work for profit… we work for the greater good. The public good.

I also wanted to say thanks for stressing me out by calling this the “distinguished” seminar series. I’m following two people that I respect very much – Trevor Dawes and Dr. Kim Christen. I watched their presentations; they were excellent. So all I’m going to try to do today is bring as much energy and insight as they did to this stage, and hopefully address any questions you have to continue this dialogue. It’s a little bit stressful but I’m also honored, so I’m gonna bring it. I promise.

One good thing about being “distinguished” is that you get to get up on a stage and talk about what matters to you. I use this image [referring to slide 10] a lot of presentations because I think it’s very evocative of the way that I tend to approach opportunities like this. I like to get up on my soapbox and holler – not quite holler exactly, but I love to discuss ideas that are challenging to our profession, that are important to the public good. And because I’m up here y’all have to listen to me, so here we go.

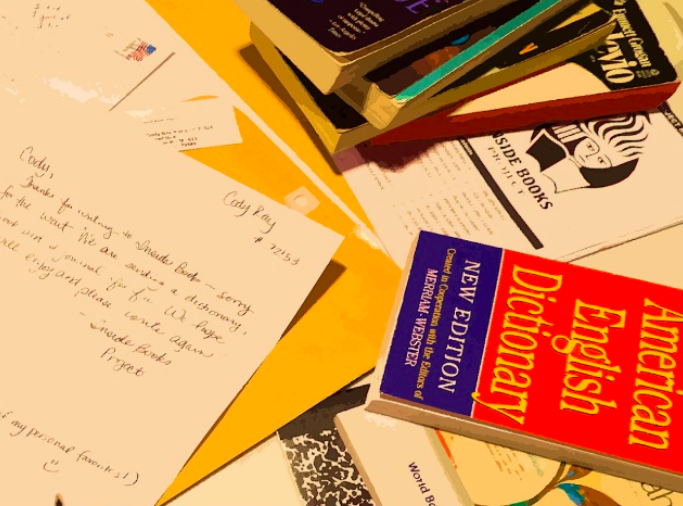

The funny thing in my preparation for this presentation – and I already mentioned this – is that I’m not a scholarly communications librarian. I have done a lot of things in my library career, but this topic is not my precise area of expertise. I took a picture of the coffee table in my hotel room this morning to give y’all a sense of how much I’ve been cramming for this for this talk.

It’s been a fascinating journey. It’s confirmed a lot of my assumptions about how OA interacts with information privilege. And it’s also tested a lot of my assumptions, taught me many things I did not know, and has given rise to some ideas that I want to throw out there that I think might be interesting.

So where do I come from in libraries? I’m a teacher. I started off as a Reference & Instruction librarian at Ohio University. This is the primary perspective I tend to bring to my work, teaching and learning, information literacy and how to challenge people to use their noodles (for lack of a better word). For the last five-to-seven years I’ve been in management and administration: I used to focus on learning exclusively, and now it’s about how to get things done and use the tools at our disposal in libraries to be sustainable and above all else support our students. And that’s where I get my inspiration, that last line – supporting students. Student learning is my primary motivation and it’s something that grounds the ideas I want to share with you today. So that’s where I get my fire.

I want to establish a central premise for this talk – it’s something that I’ve alluded to a couple of times already. This is a quote from OA advocate John Wilinsky:

“Access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend as well as advocate for other rights.”

For context, he’s won awards from SPARC, a foundation that deals with the promotion and proliferation of OA, and wrote a book called The Access Principle in 2006 that I recommend to people. It’s free, no surprise there.

I think this quote is a perfect encapsulation of how I want to come at the the two topics of OA and information privilege. This should simply be true for people in our field. Information professionals, librarians, knowledge workers – our work is predicated upon this idea. I hold it very strongly and I hope that you do too.

I want to give you quick definitions of these two concepts before I go any further. Information privilege is a relatively simple idea. Privilege itself means that – just to give you an example – I’m standing up here with my fancy shoes and I had a great breakfast and I got flown out here by OCLC, which I’m very grateful for… these are incredible advantages that I have had and accumulated over the course of my life. There was some hard work in there but the way I look, where I come from, the educational opportunities I had, the white middle-class background that I grew up in – that is the accumulation of my privilege, and I use it and I feel it every day.

Transfer that concept to the the area of information access, and people who are poor, people who are minoritized, people who are incarcerated, people who don’t have an institutional affiliation with a particular school, or have a public library close to them that offers anything like free interlibrary loan: these people are are information underprivileged, information impoverished. And OA – for this audience I don’t need to be defining it at length, but I do like the Budapest Open Access Initiative‘s definition as “the right of users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full text of content.” So, not having to pay for stuff in the simplest words possible.

Like I mentioned at the beginning, these are huge concepts. At the stratospheric level ideas of OA and information privilege can seem a little bit oblique… confusing… not really that tangible. What I want to do is bring these things down closer and closer to earth, to the point at which people who work in libraries – maybe if these aren’t your motivating factors yet – can begin to grapple with them on the ground and put activities into action that can actually help manifest more information equity and more OA that is truly open. I’ll get to that little qualifier by the end – how open is open? It’s a good question.

I like to tell stories, and I like to speak for myself. So from my own vantage point I’m going to tell you a couple of vignettes that illustrate what information privilege looks like, what information underprivilege looks like, the responsibilities of the former, and the negative effects of the latter.

I’ve lived all over the country and have had a lot of jobs – I like to move around. What I really want to talk about is the way that I was raised. That’s my mom – she’s amazing – I hope she’s watching (sometimes she is). Once Rachel [Frick] invited me to give the keynote at the 2013 Digital Library Federation conference in Austin: my mom lives in there, and she was in the audience smiling. My mom raised me with a real love of learning – she was an ESL teacher at the college level, a Spanish teacher at the college level, and she raised her kids to be autodidacts – to know how to teach ourselves. The way she did this was to instill in us an absolute love of libraries and reading.

At the same time, living in Texas I had a very difficult experience growing up. Being a queer person, I came out very young and was in a very conservative place. The instant I could liberate myself I shot across the country at light speed and landed in Portland, Oregon at Reed College, a place that encapsulated what I wanted in furthering my education. It was an extremely rigorous, self-directed, maniacally difficult place to study. Here’s another aspect of my privilege – this was expensive. I had help, and without it I wouldn’t have been able to get out of the bad situation I was in. So I’m grateful for that.

I go back home to Austin and begin the process of getting my library degree at UT, learning how to do the work. I had the opportunity to work at Perry-Castañeda Library, and shout out to all my colleagues there. At the same time I started to do the thing that sometimes one does when they’re surrounded by a community of activists and artists – I started to develop more of a political consciousness. This was growing in me from my experiences as a queer person who experienced a lot of trouble based on my identity. Combining social justice activism and libraries led me to work with a books to prisoners project called Inside Books.

Prison libraries are an established sector of our profession, but unfortunately are shrinking with the privatization of incarceration, wherein “special programs” focused on education and literacy are often eliminated. Those special programs are essential to prisoners who not only have to spend their time in these horrible boxes, but need to be able to advocate for themselves in and through the judicial system. A number of court cases enshrined the right to access to prison libraries and then knocked it back down again[1]. Prison libraries have been in trouble for a long time, and for that reason there are organizations across the country (and I assume across the world) that have programs for distributing reading material to incarcerated folks.

At Inside Books we received letters from all over prisons in Texas with notes that would say, “I’d really like this kind of book, can you please send me xyz?” We’d get requests for Spanish-language dictionaries, westerns, romance novels, chemistry textbooks – anything under the sun – and we would fulfill those requests, write a note back, and mail it off. What was so unfortunate is that a lot of the items got returned for no reason. We’d pay postage to put these books in the mail, they’d go to the prisons, and for some arbitrary reason a lot of them would get kicked back to us with “return to sender” without any rationale.

For these incarcerated people, even when external actors were trying to support them with direct donations, disenfranchisement was going on. Systematic rejection of reading materials for prisoners because… why? It’s dangerous? You tell me. The systematic rejection of books to prisoners work is an excellent example of information poverty, a concept that’s been discussed at length in our profession. It’s not just about information privilege – the flip side is that some people just simply can’t get access to the knowledge that they need in order to be able to advocate for justice for themselves and others.

Switching gears, going back to Ohio where I’m standing now. A lot of information poverty has to do with isolation. When I lived in the woods in Ohio, I had my fancy library job but I was trying to complete an online degree at the time and that house didn’t have internet. I don’t even think we could get dial-up out there. So I was like okay, online degree and no internet: this is going to be interesting. I would load up a laptop at the end of my workday with all the tabs I needed to read, and I would go home and think to myself “I hope nothing crashes” and attempt to write out my assignments in Word and then paste them into the discussion forums the next day. This is the most vanilla example of information underprivilege possible, but it goes to show you that being incarcerated isn’t the only way to not have information privilege. If you are isolated, if you live in a rural community, if you do not have proximity to libraries that have robust collections, or if you’re in communities that are having their public library budgets cut.

I wanted to tell my favorite story about triumph over information isolation. This individual [Sandor Katz] is someone I met while doing the Inside Books volunteer work – this person lived on a radical fairy land trust in the middle of nowhere in Tennessee, and his thing is fermentation. He was also ill, especially at the time that he was on this journey of figuring out how to ferment foods, and teaching other people how to do it – trying to figure out how to keep his gut bacteria healthy and feel better. This individual also has a huge brain and a lot of curiosity, so over the course of this work of figuring out how to make different kinds of fermented food he realized that a lot of the articles he needed weren’t going to be available to them, particularly not in his isolation in the woods. Over the course of his travels he had interacted with librarians, so I started getting emails from him years ago saying, “hey Char, can you maybe find me this article from the Journal of Viral Bacteriology?” or whatever. And because I was at Berkeley I was like “yeah, I’ll just send it to you.” If he hadn’t had those connections with librarians across the country to begin to lift these paywalls for him, he never would have been able to do this incredible thing that he ended up doing, which was writing a New York Times bestselling book called The Art of Fermentation, which some of you have probably read.

Okay, let’s return to an important point. This individual had to ask librarians to literally break the law for him in order to produce that book. A point I’m going to come back to again is that even though it’s ten years after this example and the OA movement has made so much progress, the same situation still exists: this is what we need to work on. And of course Sandy outed every single librarian who had helped him in his acknowledgments, which is rad because it just goes to show what we’re about and the lengths we’ll to go to to help people get that information that they need.

We have information privilege, and how are we going to use it? A good way to think about this kind of work is to:

“explain what is wrong with current social reality, identify the actors to change it, and provide achievable, attainable, practical goals for social transformation.” – James Bowman

This is a mode of thinking that helps you analyze and deconstruct power and privilege and the intersectionality of different identities that give people more and less power, more and less privilege. I like this allegory to library and information work. In order to understand and act upon a situation like Sandy’s, we need to be able to explain what is wrong (and let’s face it, there’s a lot wrong) with current social reality, identify the actors to change it, and provide achievable, attainable, practical goals for social transformation.

This is our mission, and this is what I’m going to be talking about for the rest of the presentation. How do we do this? What does this look like, and how do these two massive stratospheric ideas of OA and information privilege collide toward this goal? I’m already twenty minutes in, and because I could talk about this stuff literally until you all fall asleep and/or die I’m going to focus it down.

A thing I like to do when I’m confronted with this impossible of a topic is ask myself hard questions, which helps focus on the most meaningful things to engage during this limited amount of time we have together. The first question is important – why do we do this work? I hope that you have a good answer to this question. Think about it. I’ve begun to tell you why I do this work, but I challenge you to think about your own motivations for the energy that you put in when you’re not sitting in these chairs. Equally and more important, what values are most important to our communities? We’re libraries, and the reason we exist is to hold a mirror up to our communities and augment everything that they are and need. We should match the people we serve. We should see them, value them, and give them the things they need to thrive and be able to advocate.

And my favorite question of all – what’s broken that we can help mend or fix? I have a brilliant friend named Pascal Emmer. He’s an amazing activist and human being, and also happens to be a ceramicist that makes objects I can’t quite believe are possible. Every once in a while Pascal will fire something that explodes. This is a thing that happens to people who make pottery – my wife Lia, she’s also a ceramicist and I’ve seen her lament many an exploded piece over the course of our marriage. But that just part of it. There’s a beautiful Japanese ceramics technique called kintsugi – if your piece breaks in such a way, instead of only gluing it together you can paint the cracks over with gold to highlight the flaws. In order to make it that much more beautiful.

I want to use this broken object with obvious flaws as a metaphor for the work that we can do around information privilege and OA. I want to characterize it with this phrase – “the politics of and imperfection and responsibility.” An article came out recently by Frances Lee called Why I’ve started to fear my social with my fellow social justice activists. What this article talks about is an ethics of activism. We’re all imperfect. Our institutions are imperfect, every single thing is imperfect. We have to be able to recognize imperfection, see the cracks, and then take responsibility for fixing them. Not only fixing them, but highlighting the work that we did to fix them. Which is where the kintsugi metaphor comes back in: we want to demonstrate the brilliance of what has been broken and been put back together.

Now I get to talk about CSU San Marcos, which is a place I love very much. This is my library – it’s a huge beautiful new building and I, for most of my career, have worked in older crappy libraries that were falling apart bit by bit. It feels incredible to be in a facility that is operational, and shiny, with the carpets that are, like, decent. Tt’s great, but that’s not all there is to it. The thing about the students that I work with, and the students that the CSU system as a whole serves, is that these are students who have been minoritized for many reasons: poor students, underrepresented students. We’re an Hispanic Serving Institution with a large proportion Pell Grant recipients. It’s because of those factors that information underprivilege is a fact of life. It’s just a reality. A lot of the work that we do at my institution is geared towards what kind of economic impact that we can have on our students’ educational experience in order to help them persist.

I want to acknowledge and attribute Carmen Mitchell, who I gave a shout out to earlier. This image [of sticky notes on a whiteboard] is part of the #textbookbroke campaign that started a couple of years ago – Carmen worked on this at CSUSM. A lot of people are wise to the fact that textbooks are too expensive. Students cannot afford them, and sometimes drop out of school because of the cost. Students don’t get the textbooks they need for classes, and therefore their experience and performance is affected. So, we put up whiteboards in the entrance of our library and asked this question – “what would you be able to afford if you didn’t have to buy your textbooks?” We got hundreds of responses. Carmen did an analysis and a bit of visualization, and what we saw is things like this: “new teeth, food, housing, gas, rent”. These are basic human needs, and these are what our students have to forego – not just our students but many students in this country and internationally – in order to afford the materials of their education.

There’s a professor at CSU San Marcos that I respect named Jill Weigt, and in preparation for a panel on food insecurity she created an extra credit assignment in one of her classes. She asked students (and these were second year sophomores) “What are the three barriers to your academic success? What do you want to call out as the hardest things that confront you?” Without fail, things like “due losing my job I became homeless”, “I lack transportation”, “I was paroled from prison and I had to do all these parole things and I couldn’t make it to class,” “family obligations at home”, “stress and allocating finances to pay for school”, and, simplest of all: “culture, race, economic background.” This is reality, and as librarians and people who work in the world of information we should be focused on fixing this, because it is killing our students.

Students are experiencing external challenges, and, frankly, violence. We’re finding white supremacist recruitment posters all over my campus – these organizations are targeting schools that have a lot of underrepresented minorities. Our students are challenged from so many structural directions that they cannot control, and now this on top of all of it? It’s crushing, and it has a lot of synchronicity with the topic at hand. “Fake news”, the warping of the idea of truth itself, is feeding into this culture, and that culture is feeding into our institutions. I think libraries have the responsibility to help stem this tide, and speaking of responsibility — thanks to OCLC for my speaking fee. I donated it to an organization called Life after Hate. If anyone is interested in supporting a group that helps people who have been white supremacists rehabilitate themselves, please give them money. They were slated to get a huge federal grant a few years ago, but in the new administration that grant got cancelled, so they need money.

So can we all agree that there are cracks in the system? Can we all agree that it’s our responsibility to shine a light on these cracks and try to make them beautiful when we fix them? Excellent, I’m hearing lots of “yeses”. If the principle of our institutions is that “libraries are for everyone”, if our Bill of Rights says that libraries are about access, advocacy, openness, freedom, and inquiry, we have to acknowledge the flipside. This is the piece of the “happiness is attainable” sign that’s covered in rust. Libraries have a history of – and this was addressed in Kim Christen’s talk before me – encouraging assimilation of different cultures into American culture, of perpetuating colonialism, of being party to censorship that still happens today, biased description in our cataloging and metadata, and frankly complicity – we segregated. And the way this behavior comes out today is often in the form of fees, fines, polices, “neutrality,” and apathy on the part of library employees.

What can we possibly do to attack these big problems? Well, it’s simple – we identify and overcome the barriers that we perceive, systematically, in our institutions for our communities on the ground. I gave a talk recently at this event at CSUSM called the Social Justice Summit. It’s a group of 40 students at CSU San Marcos who sign up for an intensive three-day training in how to be effective activists. It’s about communication, fundamentals of social justice theory and criticism, and just generally being awesome. These people were very inspiring to me, and what I talked to them about is how libraries can act as allies to them, how the library itself can be an institutional ally. I want to give a couple of quick examples of the way we’re doing this at CSU San Marcos, and again this is not “my” work, this is the work of the collective and it’s something that’s very important to acknowledge. It’s never just about an individual in libraries.

So if money’s part of the barrier, what can we do? One of the proudest things that I’ve done at San Marcos is blow open the wage structure for Student Assistants at our library. Student Assistants do a huge amount of the work in libraries, and they often get paid poor wages. Federal Work Study farm, does that sound familiar than anyone? Yeah, no. That’s not cool. Our campus didn’t really allow us to give raises to students unless they’d worked a certain number of hours, and so I in my administrative privilege became very annoying to our Human Resources office and forced them to rethink because of my polite persistence about asking, Can’t we give merit raises? Can’t we hire people at at different rates?? The answer was no, but now it’s changed for the whole campus. I didn’t know that’s what was going to happen, but it’s a great thing. If you administrators out there don’t think you can do anything, you’re wrong.

And of course, affordable learning materials programs. Again, a hat tip to Carmen Mitchell. Being able to figure out ways to save our students money on textbooks, including the library renting them for a semester and checking them out on reserve. Also, eliminating fines and fees – this is a big one. We still charge people when books are lost, but why are you going to penalize someone for having a book too long? If it’s not lost, we don’t need to do that. Opening a 24 hour area in our library – this is a student-funded initiative: our student government ran a ballot referendum that pays for it. Based on the data that shows that 20% of our students are housing insecure and up to 50% of our students have experienced food insecurity, we have food, we have a comfortable situation in there and trying to make that that space as hospitable as possible. Other things we’re doing include attempting to have arts and culture programs that are representative of minoritized identities. We recently featured a Black Panthers exhibit, and hat tip to Mel Chu, Talitha Matlin, and Kate Crocker for the awesome work they did on it. We make sure that our Common Read books are representative of diverse identities and challenging topics, and are also trying to get some mural art in our building that will align with the muralist culture and tradition in San Diego.

Those are the on-the-ground examples that I wanted to give about the idea of an information justice that comes from libraries, from the work that we do on the ground, and the way that we perceive our users. This idea of information justice is a familiar one to libraries and librarians and people who work in allied nonprofit fields, and it is absolutely essential to integrate this with the idea of OA itself. I’m not going to regale you with all the figures about how many materials are published OA and how much content is available – it’s a lot. So much work has been done to create repositories where people can self-archive their content, to create advocacy organizations that promote legislation such as FASTR that mandate that people who have state or federally funded research deposit their work so that the public can find it. I do think it’s important to acknowledge the most important voices in the OA movement, including Aaron Swartz, who was famously arrested in 2011 for downloading ton of JSTOR articles at MIT, and then, extremely tragically, took his own life in 2013. Some people associate that with the legal trouble he got in, and while I cannot speak for him it was a tragic event. Aaron has this quote that I think draws us right back to our responsibility as librarians and people with so much access privilege ourselves:

“Those with access to these resources — students, librarians, scientists — you have been given a privilege. You get to feed at this banquet of knowledge while the rest of the world is locked out… But you need not — indeed, morally, you cannot — keep this privilege for yourselves. You have a duty to share it with the world.”– Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto, 2008

We have a moral obligation to share the information we have access to, and to determine how it can be shared most effectively.

In my teaching I’ve found that information literacy doesn’t resonate strongly with students unless I connect it to information privilege. I think it is fascinating that after years of teaching to people who are basically falling asleep in classrooms, the second I started talking about money – how if you’re at this school we pay x million dollars so you can have access to y amount of content, and once you’re out of here you’re cut off – they start listening. Then it becomes a structural, systemic, societal issue. This is important for the interventions we can come up with to create an effective and pervasive OA information culture. We need to be able to leverage the policy and legislation initiatives that are happening such as FASTR, which I mentioned – discovery platforms such as the DOAJ which has something like 2.6 million articles at this point from 10,000 certified legitimate non-predatory journals. Open educational resources, which I’ve talked about a couple of times. And of course digitized collections such as Hathi Trust and the Digital Public Library of America. These are quick examples, because it would take me three days to talk about all the good content that’s being developed.

But here’s where it gets dark – we have to talk about the flip side. It’s estimated that by now about 25 percent of all the academic scholarly content that’s published is available in some form of OA, and that’s that’s huge. But it still means 75% of the content is behind a paywall. Over 700 mandated OA publishing agreements have been created by research organizations institutions that basically force their faculty to put items in OA repositories or to publish gold OA (which is paying an article processing charge). Unfortunately, even with that, only 25% of content is OA, and libraries in this country still spend 3 billion dollars a year paying the top five publishers for their huge profit margins. This is an amazing statistic: since the rise of OA content (say around 2010) the profit margins of publishers like Elsevier, Blackwell, and Wiley have gone up 10%. Their margins started at 30% and now they’re hovering around 40% – this makes inverse proportional sense. What it means is that there’s a there’s a co-opting of OA by these monster publishers. It highlights a pressing need in our field and allied fields – nonprofit, information-focused fields – to figure out why publishers are profiting so much from OA content, and how it is that a larger and larger share of our purchasing budgets are going to them.

Now that I’m an administrator I truly see the impact this has on our institution. We want to be able to hire more teaching faculty, we want to be able to do more cultural and public programming, but we’re curtailed by the meteoric inflation rise like everyone else. This doesn’t only affect academic institutions. I wanted to quote Roger Schonfeld of Ithaka S&R – “publishers appear to have largely co-opted open access… there’s little evidence that a way has led to decreased licensing expenditures, and it is almost certainly led to a boom at least for the short term in content revenues for some of the largest publishers.” So if journal content prices have outpaced inflation by 250% in the last 30 years – this is intense – what are we going to do about it? And what are other people doing about it out there in the world?

I’ll tell you one thing they’re doing: they’re pirating the hell out of it. Does anyone know who this is this is? It’s Alexandra Elbakyan. She’s the neuroscientist who invented SciHub. There’s a movement on Twitter called #icanhazpdf, which is like an army of Sandys requesting PDFs from colleagues and people trading articles informally online. Along comes Alexandra Elbakyan, who and invents a way to steal 50 million academic articles and make them freely available on the open web. The programming behind this is so diabolical that it’s ingenious. The program is pilfering our own licensed content and adding it to SciHub. There’s an allied site called Library Genesis that has two million volumes of mostly humanities content. Of course SciHub and Library Genesis get a lot of challenges from publishers in the form of lawsuits. One in 2015 ordered SCI hub to come down – it went down and came right back up at about two weeks under a different domain.

Academics are grappling with what it means to have all this pirated content out there, and our relationship to these movements that are literally trying to free information but doing so in very much illegal and illegitimate ways. I encourage anyone who’s interested in this topic to read Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone, which came out in Science. It shares statistics like the fact that 28 million papers were downloaded from SCI hub over a period of six months in 2016, that fifty million papers have been indexed by that date – and here’s the most important part for librarians – a lot of this activity is happening at our colleges and universities, in our buildings. They created a heat map analysis of where the highest number of downloads are happening – near and at major research universities around the world and in the United States. Think about that for a minute. Three billion dollars annual in annual expenditures on journal content, and there are folks on our own campuses downloading illegally for free. Why? Because it’s easy. Because it’s discoverable, because there’s one place – only one place – that they have to go to search and download instantly. It’s illegal, but it’s easy.

I think this points to a huge challenge – and also a huge opportunity – for libraries and the organizations that work with us, to address this problem. Closed content is more readily available than the content we license. The open content we license is so challenging to access. Also, the legitimate OA content is challenging to access – because of all of those repositories and discovery tools and layers, it’s basically diffused throughout the universe. I had to do so much research for this presentation (and I’m a librarian) just to figure out what these things are called. ROAR, SOAR, etc. – I imagined being an undergraduate student basically standing out in the woods saying, “what is this? What am I searching? It’s still very confusing. I don’t mean to knock any of the efforts that have been done around OA to date. That said, I don’t think that we have yet addressed this challenge: why is the illegal stuff so much easier to get to than A) our own licensed content and B) the open content that’s sitting around in repositories, paid for through exorbitant article processing charges (APCs)? This is indeed a big challenge, and we need to figure out how to solve it.

I wanted to profile a couple of people who are already doing this – shout out to Open Access Button. We’re evaluating our interlibrary loan workflows using this tool, which is kindof like a legal analogue to SciHub. It crawls green open access publications (which of course are the ones that people self archive as opposed to gold, wherein publishers making something OA funded by APCs. The OA Button is great because if you click it and the article that you’re searching for (using a DOI or a title) isn’t available, they have a workflow that seeks out and pings that author who created the content it tries to guilt-trip them into making it available. It works. I looked through the requests and there’s a bunch of them that are successful. You can see who’s denied and who’s pending, and librarians can contribute to this project.

There are other services that do similar work, like OAdoi. There’s a SFX discovery layer that can help prioritize and push up away content in a library’s own holdings, but we still come back to this idea that these tools only cover about half of the OA universe – only the green content, only the things that article that authors have taken upon themselves to archive. Not the gold stuff, the stuff that the publishers have figured out how to co-opt and produce, the stuff that Roger Schonfeld was talking about. We need to figure out as a collective how to tackle this problem. How to have a discovery tool, layers, methods, workflows, and funding infrastructures that allow us to represent easily and in readily available sources the entire universe of OA content. This is the way to actually and actively combat information privilege especially, in our academic institutions.

So how does it happen? There has been good work done on this question. John Wenzler describes the issue as the “collective action dilemma.” This is one of the barriers that he sees to why libraries haven’t solved this problem yet. It’s the tragedy of the commons: who’s going to pay for it, who’s going to organize it, who’s going to make this work sustainable. K | N consultants – that’s Rebecca Kinnison and Karen Norburg – created a whitepaper that proposes how to revitalize and change the infrastructure of scholarly communication via institutions paying flat annual fees into a giant pool. They did the math in this huge spreadsheet – it’s beautiful – with the price breakdown for the thousand schools they index, and it comes out to about sixty million dollars annually. So instead of paying increasing inflation charges, maybe we can start banding together privileged OA content creation tools that actually help people discover this content easily. This will give us more leverage to negotiate with publishers who keep jacking up prices, and help give people OA content that they’ll actually be able to keep after they leave our institutions.

If there’s a collective action dilemma, then we have to work together to solve it. This work is ongoing, and the content foundation of OA has been laid and is here to stay. There are thousands of repositories and hundreds of agreements helping authors archive, but discovery is still a problem. It’s so much of a problem that our own faculty can’t even figure it out, and they go through more nefarious means to get their information.

To wrap up: if we acknowledge the politics of imperfection and responsibility, if we’re looking for cracks in the system and ways to take responsibility for and challenge information privilege and information poverty by creating a reliable and sustainable infrastructure for OA, then we have to use the same logic that libraries around the world do: figure out how to help patrons overcome the barriers in their lives. If discovery is a problem, if collective action is a problem, who’s going to take up the charge? This is a question we’re still trying to answer, but it’s all geared towards the end goal I began with: information equity.

To close on a positive note, I wanted to give it quote from Toni Morrison. This is where I try to eject you from your seats so you run back to your desks get this thing done, right now:

“When you get these jobs that you’ve been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.” – Toni Morrison

And that is my presentation.

[1] Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817 (1977), mandated that prisons provide incarcerated people with access to legal professionals or law library collections – this preserved the right of “meaningful access to the courts.” Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343 (1996), rolled this requirement back. A discussion of impacts of these cases and other trends in US prison libraries is available in Lehmann, V. (2011). Challenges and accomplishments in U.S. prison libraries. Library Trends, 59(3), p. 490–508.

References/Works Consulted:

Bergstrom, T. C., Courant, P. N., McAfee, R. P., & Williams, M. A. (2014). Evaluating big deal journal bundles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(26), 9425-9430. Retrieved from http://www.pnas.org/content/111/26/9425.full.pdf

Bohannon, J. (2016). Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone. Science, 352(6285), 508-512.

Britz, J. J. (2004). To know or not to know: A moral reflection on information poverty. Journal of Information Science, 30(3), 192-204. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0165551504044666

Cope, J. (2016). The labor of informational democracy: A library and information science framework for evaluating the democratic potential in socially-generated information. In B. Mehra & K. Rioux (Eds.), Progressive community action: Critical theory and social justice in library and information science. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed. (Ramos, M. B., Trans.). London: Penguin Books.

Gardner, C. C., & Gardner, G. J. (2015). Bypassing interlibrary loan via Twitter: An exploration of #icanhazpdf requests. In Proceedings of ACRL 2015. Portland, Oregon, March 25-28, 2015. Retrieved from http://eprints.rclis.org/24847/

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Kennison, R., & Norberg, L. (2014). A scalable and sustainable approach to open access publishing and archiving for humanities and social sciences. A white paper. New York: K|N Consultants. Retrieved from http:// http://knconsultants.org/toward-a-sustainable-approach-to-open-access-publishing-and-archiving/

Land, R., Meyer, J. H. F., & Smith, J. (Eds.) (2008). Threshold concepts within the disciplines. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.sensepublishers.com/media/1179-threshold-concepts-within-the-disciplines.pdf

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLoS ONE, 10(6): e0127502. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

Lewis, D. W. (2017). The 2.5% commitment. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1805/14063

Ruff, C. (2016). Librarians find themselves caught between journal pirates and publishers. The Chronicle of Higher Education 62(24). Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Librarians-Find-Themselves/235353

Schonfeld, R. (2017). Red light, green light: Aligning the library to support licensing. Ithaka S+R, Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.304419

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/9780262517638_Open_Access_PDF_Version.pdf

Swartz, A. (2008). Guerilla open access manifesto [Online resource]. Retrieved from http://openscience.ens.fr/DECLARATIONS/2008_07_01_Aaron_Swartz_Open_Access_Manifesto.pdf

Tennant, J. P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D. C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L. B., & Hartgerink, C. H. (2016). The academic, economic and societal impacts of open access: An evidence-based review. F1000Research, 5. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4837983/

Wenzler, J. M. (2017). Scholarly communication and the dilemma of collective action: Why academic journals cost too much. College & Research Libraries, 78(2), 183-200. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.2.16581

Willinsky, J. (2006). The access principle: The case for open access to research and scholarship. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Retrieved from http://arizona.openrepository.com/arizona/handle/10150/10652

Leave a comment